Eating Disorders: When Outpatient Treatment Is Not Enough

Eating disorder treatment is a long-term process involving a potentially life-threatening situation. Treatment is extremely expensive with therapy most likely extending well over two years. Most eating disorder treatment takes place on an outpatient basis. Outpatient therapy refers to individual, family, or group therapy sessions taking place in a therapist's or other professional's office and is usually conducted one to three times per week. Individual sessions generally run forty-five minutes to an hour, and family or group sessions are usually sixty to ninety minutes. Sessions can be arranged for more or less time if needed and as deemed appropriate by the treating professional. The cost of outpatient treatment, including eating disorders therapy, nutritional counseling, and medical monitoring, can extend to $100,000 or more.

There may come a time when outpatient treatment is insufficient or contraindicated due to the severity of the eating disorder. Treatment in a more intense structured setting, such as a hospital or residential facility, may be required when eating disorders symptoms are out of control and/or the medical risks are significant. If treatment necessitates a round-the-clock or more acute program, such as an inpatient hospital stay, this alone can be $30,000 or more per month with some patients needing several months or repeated hospitalizations.

Most people consider a treatment program as a last resort; however, if specifically designed for eating disorders, this kind of program can be an excellent option even in the beginning of treatment. There are a variety of settings that provide more intense levels of care than outpatient therapy. When looking for a treatment program it is important to understand the difference between the intensity and structure of different levels of care. The various options include inpatient, partial hospitalization or day treatment programs, residential treatment facilities, and halfway or recovery houses. These options will be described below.

Eating Disorder Treatment Program Options

Inpatient Treatment

Inpatient eating disorders treatment means twenty-four-hour care in a hospital setting, which can be a medical or psychiatric facility or both. The cost is usually quite high, around $1,200 to $1,400 per day. Inpatient treatment at a strictly medical hospital is usually a short-term stay to treat medical conditions or complications that have arisen as a result of the eating disorder. In some cases, a patient may stay longer simply because her medical condition is severe. In other cases, patients stay longer in a medical hospital than is medically necessary because there is no other facility close by to treat the patient. This is particularly true if the hospital has provisions or a treatment protocol for eating disorders. The rest of the inpatient treatment of eating disorders takes place in psychiatric hospitals that utilize nearby or associated medical facilities when necessary. It is very important that these psychiatric hospitals have trained eating disorder professionals and a treatment program or special protocol for treating eating disorders. Treatment in a hospital without specialized care for eating disorders will not only be unsuccessful but can cause more harm than good.

Partial Hospitalization or Day Treatment

Often individuals need a more structured program than outpatient treatment but do not need twenty-four-hour care. Additionally patients who have been in an inpatient program can often step down to a lower level of care but are not ready to return home and begin outpatient treatment. In these cases partial programs or day treatment programs may be indicated. Partial programs come in a variety of forms. Some hospitals offer programs a few days per week, or in the evening, or a few hours each day. Day treatment generally means the person is in the hospital program during the day and returns home in the evening. These programs are becoming more prevalent, in part due to the cost of full inpatient programs and also due to the fact that patients can receive great benefits from these programs without the additional burden or stress of having to leave home entirely. Due to the amount of variation in these programs it is not possible to give a fee range.

Often individuals need a more structured program than outpatient treatment but do not need twenty-four-hour care. Additionally patients who have been in an inpatient program can often step down to a lower level of care but are not ready to return home and begin outpatient treatment. In these cases partial programs or day treatment programs may be indicated. Partial programs come in a variety of forms. Some hospitals offer programs a few days per week, or in the evening, or a few hours each day. Day treatment generally means the person is in the hospital program during the day and returns home in the evening. These programs are becoming more prevalent, in part due to the cost of full inpatient programs and also due to the fact that patients can receive great benefits from these programs without the additional burden or stress of having to leave home entirely. Due to the amount of variation in these programs it is not possible to give a fee range.

Residential Facilities for Eating Disorder Treatment

The majority of eating disordered individuals are not medically unstable or actively suicidal and do not require hospitalization. How-ever, a substantial benefit may be received if these individuals can have supervision and treatment on a twenty-four-hour-per-day basis of a different nature than hospitalization. Binge eating, self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse, compulsive exercise, and restricted eating do not necessarily lead to acute medical instability and thus do not qualify by themselves as criteria for hospitalization. If this is the case, many insurance companies will not pay for hospitalization since coverage often requires the individual to be dangerously medically compromised. However, eating disorder behaviors can become so habitual or addictive that trying to reduce or extinguish them on an outpatient basis can seem almost impossible. Residential eating disorders treatment facilities offer an excellent alternative, providing round-the-clock care in a more relaxed, affordable, nonhospital setting.

Residential facilities vary greatly in the level of care provided, so it is important to investigate each program thoroughly. Some programs offer sophisticated, intensive, and structured treatment very similar to a hospital inpatient program but in a more relaxed environment and in some cases even a renovated house or estate. These facilities often utilize physicians and nurses, but not on a twenty-four-hour-per-day basis, and the residents are referred to as clients, not patients, as they are medically stable, not requiring acute medical care. Other residential facilities are less structured and provide far less treatment, often centered around group therapy. This type of residential program falls somewhere above recovery or halfway houses (see below) but with less structure than the type of residential program described here.

Some individuals go directly to residential treatment programs, while others spend time in an inpatient facility and then transfer to a residential program. Residential treatment is becoming very popular as a choice for treating eating disorders. One reason for this is the cost. Some residential programs charge as little as one-third of the fees of most inpatient facilities. Cost varies but is usually between $400 to $900 per day. Furthermore, residential programs can offer a crucial and important treatment feature not feasible in an inpatient setting. In some (but not all) residential settings, patients have the opportunity to be increasingly involved in meal planning, shopping, cooking, exercise, and other daily living activities in which they will need to participate upon returning home. These are problem areas for eating disordered individuals that cannot be practiced and resolved in a hospital setting. Residential facilities offer treatment and supervision of behaviors and daily living activities, providing clients with increasing responsibility for their own recovery.

Halfway or Recovery House

A halfway or recovery house can easily be confused with residential treatment, and in some cases there is a fine line of distinction between them. Recovery houses have far less structure than most residential programs and are usually not equipped for individuals who are still engaging in symptomatic eating disorder behaviors or other behaviors needing a good deal of supervision. Recovery houses are more like transitional living situations where residents can live with others in recovery, attending group therapy and recovery meetings and participating in individual therapy either as part of the house program or with an outside therapist. The idea was originally developed for drug and alcohol addicts so they could have a place to live with other recovering addicts attending group therapy and/or recovery meetings under the supervision of a "house parent." This was designed to help individuals practice sober living skills before going back to live with their families or on their own. These recovery homes are far less expensive than hospitals and even less than residential facilities. Fees can range from as little as $600 up to $2,500 per month, depending on the services provided. However, it must be kept in mind that most halfway or recovery houses provide far less treatment and supervision than is necessary for many eating disordered individuals. This option seems useful only after a more intensive treatment program has been successfully completed.

When to Use 24-Hour Care

It is always the best circumstance when an individual chooses to enter into a treatment program by choice and/or before it becomes a life-or-death situation. A person may decide to seek treatment in a hospital or residential setting in order to get away from the normal daily tasks and distractions and focus exclusively and intensely on recovery. However, it is often as a result of medical evaluation or a crisis situation that the decision to go to, or put a loved one in, a treatment program is made. To avoid panic and confusion, it is important to establish criteria for and goals of any hospitalization ahead of time, in case such a situation arises. It is essential that the therapist, physician, and any other treatment team members agree on hospitalization criteria and work together so that the patient sees a competent, complementary, and consistent treatment team. The criteria and goals should be discussed with the patient and significant others and, when possible, agreed on at the beginning of treatment or at least prior to admission. Involuntary hospitalization should be considered only when the patient's life is in danger.

In relation to the specific eating disorder behaviors, the primary goal of twenty-four-hour care for the severely underweight anorexic is to institute refeeding and weight gain. For the binge eater or bulimic, the primary goal is to establish control over excessive binge eating and/or purging. Hospitalization may be needed to treat coexisting conditions such as depression or severe anxiety that are impairing the individual's ability to function. Furthermore, many eating disordered individuals experience suicidal thoughts and behaviors and need to be hospitalized for protection. A patient may be hospitalized strictly for a medical condition or complication such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, fluid retention, or chest pain, in which case a medical hospital may be sufficient. The decision regarding where to hospitalize must be decided on a case-by-case basis. When hospitalization is intended to address any of the eating disorder issues, it is important to look for a treatment program or hospital unit specializing in the care of eating disordered patients. Below are some guidelines as to when a decision to hospitalize might be made.

SUMMARY OF REASONS FOR HOSPITALIZATION

- Postural hypotension (low blood pressure).

- Cardiac dysfunctions such as irregular heartbeat, prolonged QT interval, ventricular ectopy.

- Pulse less than 45 beats/minute (BPM) or greater than 100 BPM (with emaciation).

- Dehydration/electrolyte abnormalities such as a serum potassium level less than 2 milligrams equivalents per liter, fasting blood glucose level less than 50 milligrams per 100 milliliters, creating a level greater than 2 milligrams per 100 milliliters.

- Weight loss of more than 25 percent of ideal body weight or rapid, progressive weight loss (1 to 2 pounds per week) in spite of competent psychotherapy.

- Binge/purge behaviors are happening multiple times per day with no or little reduction.

- Outpatient treatment failure: (a) patient is unable to complete an outpatient trial, for example, can't physically drive to or remember sessions, or (b) treatment has lasted six months with no substantial improvement (e.g., weight gain, reduction of binge eating or purging, etc.).

- Observation for diagnosis and/or medication trial.

- Suicidal thoughts or gestures (e.g., self-cutting).

- Chaotic or abusive family situation, in which the family sabotages treatment.

- Inability to perform activities of daily living.

By Carolyn Costin, MA, M.Ed., MFCC

- Medical Reference from "The Eating Disorders Sourcebook"

Hospitalization should not be regarded as an easy or final solution to an eating disorder. Minimally, hospitalization should provide a structured environment to control behavior, supervise feeding, observe patient after meals to reduce purging, provide close medical monitoring if needed, and, if necessary to save a life, provide invasive medical treatment. Ideally, treatment programs for eating disorders should offer an established protocol and a trained staff and milieu that provide empathy, understanding, education, and support, facilitating cessation or dramatic reduction of eating disorder symptoms, thoughts and behaviors. For this reason, hospitalization does not have to be a last resort. In fact, professionals should avoid the connotation that indicates, "If you get too bad, or if you don't improve, I'm going to have to hospitalize you, and I know you don't want that." Hospitalization should not be feared nor should it be seen as a punishment. It is better for individuals to understand that if they are unable to battle their eating disorders with outpatient therapy alone, then more help for them will be sought in a treatment program where they will be provided the care, nurturing, and added strength they need to overcome their oppression by their eating disorders. When framed to the patients as "an opportunity to take the necessary time out from other responsibilities to focus on recovery in a setting where your thoughts and behaviors are understood," hospitalization or some other round-the-clock treatment option can be viewed as a welcomed, albeit scary, choice individuals make from the healthy part of them that wants to get better.

Letting eating disordered individuals be included in all of their treatment decisions, including when to go to a treatment program, is valuable. Control issues are a consistent theme seen in individuals with eating disorders. It is important not to let a "me against them" relationship develop between the therapist or treatment team and the person with the eating disorder. The more control individuals have in their treatment, the less they will need to act out other means of control (e.g., lying to the therapist, sneaking food, or purging when not being observed). Furthermore, if an individual has been included in the decision-making process regarding hospitalization or residential treatment, there is less trouble getting compliance when admission is necessary. Consider the following example.

Alana, a seventeen-year-old high school senior, first came in for eating disorder therapy when she weighed 102 pounds. Alana's mother brought her to see me because of her concern for Alana's recent weight loss and her fear that Alana was overly restricting her food intake, having taken her diet too far for her 5' 5" frame and her propensity for exercise. Alana was reluctant and angry that her mother had dragged her to a therapist's office; "It's my mother who has a problem, not me. She won't get off my back."

I sent Alana's mother out of the room and asked Alana if perhaps there was anything I could possibly help her with since she and I both had at least another thirty minutes to kill. When Alana couldn't really think of anything, I suggested that one thing I might do is help her get her mother off her back. This, of course, perked her up a little and she immediately agreed. After talking to her for a while and explaining how I work on getting parents to stay out of their kid's eating, I invited Alana's mother in and explained to both of them that, for right now, as long as Alana was going to be seeing me there would be no reason for her mother to discuss her eating habits or her weight. Her mother was unhappy about this and offered several protests, but I held firm that this was no longer her territory and that her involvement in fact made matters worse, which she conceded. However, Alana's mother needed reassurance that Alana would not be allowed to starve herself to death, which was an almost obsessive fear for this parent due to the recent unexpected death of her husband. Therefore, I told them that I would not allow Alana's condition to worsen without more intense intervention and that I was sure Alana had no intention of that, either. Here is where I let Alana in on a major treatment decision:

Carolyn: Alana, at what weight do you think you would need to be hospitalized?

Alana: I don't know, but I'm not going to let that happen. I'm not going to lose any more weight. I've already told everybody that. I don't need to go to a hospital.

Carolyn: Okay, so you've agreed to not lose more weight, but you're a smart girl. To reassure your mom, let her know that you do have some idea of what would be unreasonable or unhealthy to the point where you would need to go to a treatment program for more help.

Alana: (Fidgeting a bit and looking uncomfortable, not willing to say anything, most likely for fear of being trapped and held to it.)

Carolyn: Well, do you think 80 pounds would be taking it too far? Would this be so low that you need to go to a hospital then?

Alana: Of course, I'm not stupid. (Most, but not all, anorexics think they can control the weight loss and don't imagine they will ever be at the extreme weight often seen in other anorexics.)

Carolyn: I know, I already said I thought you were smart. So do you think 85 pounds would be too low?

Alana: Yes.

Carolyn: What about 95?

Alana: (Now Alana really squirms. She is trapped. She doesn't want to continue this, as it is getting too close to her current weight and perhaps she desires to lose "just a little bit more.") Well, no not really. I don't think I'd need a hospital or anything but it's not going to happen anyway.

Carolyn: (At this point I know I have her in a position to settle on a weight criterion for going into a treatment program.) Okay, so I think we can agree that you think that 85 is too low but 95 is not, so somewhere in between there you would cross the line where outpatient therapy wouldn't be working and you'd need something else. In any case, you are willing to stay at your current weight of 102. Is that right?

Alana: Yes.

Carolyn: So then for your mom's sake and since you have said you will not lose any more weight, let's make an agreement. If you do lose weight to the point where you get down to, say, 90 pounds, you will in essence be telling us that you cannot stop and therefore you need to go to a treatment program?

Alana: Sure, yeah, I can agree to that.

Throughout this discussion Alana played a major role in decision making for her treatment. She got to have her mom "off her back," and she helped determine the weight criterion for hospitalization. I did have to spend some time with Alana's mother to reassure her that this was the best approach and that letting Alana in on this criterion would help us out in the event that hospitalization was necessary. I also wanted to give Alana the chance to maintain her weight and improve her diet through outpatient therapy. However, in Alana's case, the writing was on the wall. All of Alana's behaviors described to me earlier in the session by her mother pointed to the fact that she probably would indeed continue to lose weight because, as with most anorexics, her extreme fear of gaining would keep her restricting to the point where she would most likely continue to lose. Alana did get down to 90 pounds and reluctantly, though compliantly, went into a treatment program. The process of having Alana establish the weight criterion made a huge difference in her willingness to go when it became necessary. Additionally, there was no panic or crisis when the time came, and the therapeutic relationship bond was not disrupted by me "doing something to her" or fostering the "me against them" attitude I discussed earlier. I reminded Alana that she herself had agreed that if her weight were to get this low, it would mean that she needed more help.

In Alana's case there was no medical condition or emergency situation necessitating hospitalization. Rather, hospitalization was followed through with when outpatient therapy was not working and an eating disorder treatment program was a means for her to get the help she really needed to get better. A good eating disorder program provides not only structure and monitoring but also a number of curative factors that facilitate eating disorders recovery.

Curative Factors of Inpatient or Residential Treatment for Eating Disorders

(The term patient or inpatient will be used to refer to an individual in a round-the-clock treatment program, and the term hospital, or hospitalization will refer to any round-the-clock program.)

A. SEPARATES PATIENT FROM HOME LIFE, FAMILY, AND FRIENDS

- Family members may have had a significant role in the development or sustaining of the disorder. Secondary gains with the family or with friends may be exposed and may even diminish when patients are removed from those people.

- The therapist can take a more active role as both authoritarian and nurturer and facilitate the necessary trust and relationship needed for recovery.

- When the patient is absent from the family, the therapist can see the functional significance that the patient had in the family. The "role" the patient plays in the family may be an important aspect of treatment. Furthermore, how the family functions without the patient will be helpful in determining causes and treatment goals.

- Being away from normal routines such as work, taking care of children, and daily living responsibilities, which often serve as distractions from dealing with the issues and behaviors, can help patients to focus attention where it is needed.

B. PROVIDES A CONTROLLED ENVIRONMENT

- Putting a patient in a controlled environment exposes otherwise hidden issues such as food rituals, laxative abuse, rigidity in eating behaviors, mood around mealtimes, reactions to weighing, and so on. Exposing the patient's true patterns and behaviors is necessary in order to deal with these issues, discovering the meaning they have for the patient and finding alternative, more suitable behaviors.

- A controlled, structured environment assists the patient in breaking addictive patterns. Popcorn and frozen yogurt diets will not be able to be continued. Vomiting directly after meals will be difficult in programs providing direct supervision after meals. Weight is usually monitored and yet kept from the patients in order to protect them from their own reactions to the information and to break them from being addicted to weighing and to the number on the scale. Furthermore, having a certain schedule to follow, including planned meals, helps reintroduce structure into what is often a chaotic pattern. A healthy, realistic schedule may be learned and then utilized on returning home.

- Another useful aspect of the controlled environment is medication monitoring. If medication is warranted, such as an antidepressant, it can be more carefully monitored as to compliance, side effects, and how well it is working. Observation of the reaction to medication, blood tests, and dosage adjustments is more easily carried out in a hospital setting.

C. OFFERS SUPPORT FROM PEERS AND A HEALING ENVIRONMENT

- Patients in a treatment program are there with other individuals with similar issues, problems, and feelings. The camaraderie, support, and understanding of others are well-documented healing factors.

- A good treatment team in a hospital also provides a healing environment. Its members can be positive role models for self-care and can be an example of a healthy "family" system. The treatment team can provide a good experience of the balance between rules, responsibility, and freedom.

The duration of time spent in a treatment program will depend on the severity of the eating disorder, any complications, and the treatment goals. Inpatient treatment dealing with the eating disorder should include family and/or significant others throughout its course unless the treatment team determines there is good reason not to do so. Prior to discharge, family members can work with the treatment program staff to establish treatment goals and realistic expectations for the entire family.

Hospitalization can help break any addictive patterns or cycles and start a new behavioral process for the patient, but it is not the cure. Long-term follow-up is necessary. Success rates for hospitalization are hard to come by, but there are many aspects to choosing the right program, which will not be the same for everybody.

The cost of inpatient eating disorder treatment is anywhere from $15,000 to $45,000 per month or more, and, sadly enough, many insurance companies have exclusions in their policies for eating disorder treatment, which some have referred to as a "self-inflicted" problem. Careful assessment of cost and reimbursement possibilities should be done prior to admission unless there is an emergency situation. This is an outrage to people familiar with those suffering and/or those treating these individuals. There are some recovery homes or halfway houses that charge far less, even as little as $600 to $2,500 per month. However, these programs are not as intense or highly structured and are inadequate for individuals needing higher levels of care. These programs are useful as a step down from more intensive treatment. When considering admission to a treatment program it is important to review the philosophy, staff, and schedule of various program options. To help patients and their families in the selection of an appropriate treatment program, the following "ingredients" were developed by Michael Levine, Ph.D.

Ingredients of a Good Eating Disorder Treatment Program

- Nutritional counseling and education designed to restore and maintain a body weight normal for that person. This is a body weight the person can maintain easily without dieting and without being obsessed with eating.

- Behavioral lessons designed to teach eating patterns that restore control to the person's body, not to some diet or some cultural ideal of slenderness. In other words, cognitive-behavioral lessons in how to live with food, stop black-and-white thinking, deal with perfectionism, and so forth.

- Some form of psychotherapy aimed at overcoming the eating disordered person's characteristic overvaluation of weight and shape as central determinants of self-worth. In general, this psychotherapy will address pathological attitudes about the body, the self, and relationships. The focus here is on development of a person, not refinement of a "package."

- Individual and group psychotherapy that helps the person not only renounce illness but also embrace health. In this regard, the person will probably need to learn (a) how to feel and to trust, and (b) specific skills for assertion, communication, problem solving, decision making, time management, and so forth.

- Psychiatric evaluation and monitoring. Where it has been deemed appropriate after a careful psychiatric evaluation, judicious use of antidepressant medication, for example, fluoxitene (Prozac) or antianxiety medication, or other medication to correct biochemical abnormalities or deficiencies.

- Some form of education, eating disorder support, and/or therapy that helps family and friends assist in the process of recovery and future development.

- Step-down levels of care are provided, offering increased freedom and responsibility to the patient for recovery. The key is that continuation and intervention be the same treatment team, and care involves and addresses relapse.

This list of ingredients is a good guide, but choosing a treatment program will still be a difficult decision to make with many factors to consider. The following questions will provide additional information that is useful in making the right decision.

- What is the overall philosophy of treatment, including the program's position on psychological, behavioral, and addictive approaches? ?

- How are meals handled? Is vegetarianism allowed? What happens if the meal plan isn't followed?

- Is there an exercise component other than walks or recreational activities?

- How many patients have been treated and/or are some available to speak with you?

- What kind of background and qualifications do staff members have? Are any or many recovered?

- What is the patient schedule (e.g., how many and what kind of groups are held daily, how much leisure time is there? how much supervision versus treatment takes place)?

- What step-down levels of care are provided, and what are the arrangements for individual therapy? Who performs it and how often?

- What are the outpatient or aftercare treatment and follow-up services? What is considered noncompliance, and what are the consequences?

- What is considered to be the average length of stay and why?

- What are the fees? Are there any extra fees besides those quoted that may occur? How are fees and payments arranged?

- What books or literature are given or recommended?

- Is it possible to meet with a staff member, visit a group, or talk to current patients?

Since different patients will be looking for different things in a treatment program, providing the "right" answers to the above questions is not possible. Individuals considering a treatment program for themselves or a loved one should ask the questions and get as much information as they can from various programs in order to compare options and select which program is most suitable.

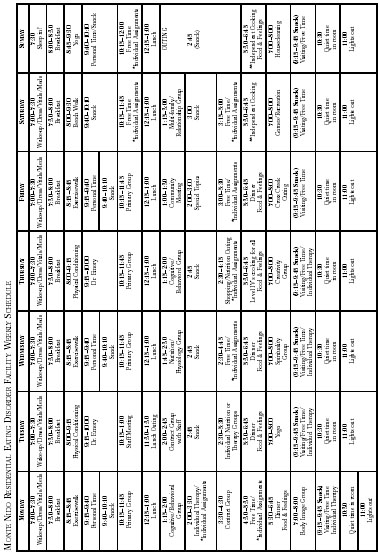

The following information on Monte Nido, my residential program in Malibu, California, provides an idea of the philosophy, treatment goals, and schedule of a twenty-four-hour care facility specializing exclusively in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and activity disorders.

Monte Nido Treatment Facility

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Eating disorders are progressive and debilitating illnesses requiring medical, nutritional, and psychological intervention. Individuals suffering from eating disorders often need a structured environment to achieve recovery. However, all too often a person does well in a highly structured, regimented environment only to fall into relapse upon returning to a less structured situation. Our residential program is designed to meet the individual needs of clients and their families in a way that gives them a higher level of responsibility and "teaches" them how to recover. The atmosphere at Monte Nido is professional and structured, but it is also warm, friendly, and family like. Our dedicated staff, many of whom are recovered themselves, serve as role models, and our environment inspires people to commit to overcoming obstacles that are interfering with the quality of their lives.

The program at Monte Nido is designed to provide behavior and mood stabilization, creating a climate where destructive behaviors can be interrupted. Clients can then work on the crucial underlying issues that caused and/or perpetuate their disordered eating and other dysfunctional behaviors. We provide a structured schedule with education, psychodynamic, and cognitive behavioral therapy; corrective eating patterns; healthy exercise; life skills training; and spiritual enhancement, all in our beautiful, serene country setting.

Our treatment philosophy includes restoring biochemical functioning and nutritional balance, implementing healthy eating and exercise habits, changing destructive behaviors, and gaining insight and coping skills for underlying emotional and psychological issues. We believe that eating disorders are illnesses which, when treated correctly, can result in full recovery where the individual can resume a normal, healthy relationship to food.

Nutrition and exercise are not simply a part of our program. We recognize these as crucial areas of recovery. Therefore, we require assessments on nutritional status, metabolism, and biochemistry, and we teach patients what this information means in terms of their recovery. Our exercise physiologist and fitness trainer perform thorough assessments and develop a fitness plan suitable for each client's needs. Our detailed attention to the nutrition and exercise component of treatment reveals our dedication to these areas as part of a plan for a healthy, lasting recovery.

Every aspect of our program is designed to provide clients with a lifestyle they can continue on discharge. Along with traditional therapy for eating disorders and treatment modalities, we deal directly and specifically with eating and exercise activities that can't be adequately addressed in other settings but, nevertheless, are crucial for full recovery.

Planning, shopping, and cooking meals are all part of each client's program. Dealing with these activities is necessary since they will have to be faced on returning home.

Clients participate in exercise according to individual needs and goals. Exercise compulsion and resistance are addressed with the focus on developing healthy, noncompulsive, lifelong exercise habits. We are uniquely set up to meet the needs of athletes who require specialized attention in this area.

Activities include weight training, water aerobics, yoga, hiking, dance, and rehabilitation for sports injuries.

Individual and group therapy establish and solidify the other treatment components. Through intensive individual sessions and group work, clients gain support, insight into their problems, and the ability to transform them. Increasing confidence is gained in appropriately selecting meals and exercise activities, while using other methods to deal with underlying issues. Outings and passes are provided to assess each client's growth in handling real-life situations. On returning from an outing or pass, clients process their experience in both individual and group sessions in order to learn from it and plan for the future.

Group topics include:

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

- Communication Skills

- Self-esteem

- Stress/Anger Management

- Body Image, Women's Issues

- Art Therapy

- Assertiveness Family

- Therapy

- Sexuality and Abuse

- Life Skills

- Career Planning

We are innovative and unique. Our director, Carolyn Costin, M.A., M.Ed., M.F.C.C., recovered herself for more than twenty years, has many years of experience as a specialist in the field of eating disorders. Her extensive expertise, including a directorship of five previous inpatient eating disorder treatment programs, combined with her unique, hands-on empathetic approach, has achieved high success rates with full recovery. Carolyn and our staff can empathize, offer hope, and serve as role models while providing skills for recovery.

LEVEL SYSTEM

Our level system allows for increased freedom and responsibility as clients progress in the program. All clients have a written contract which they help create. The contract shows the current level they are on and spells out the goals for that level. Each client's program is individualized even though there are certain activities, reading assignments, and other requirements for every level. A copy of the contract is given to each client, and one is kept in the client's chart.

Special privileges. If deemed appropriate, clients may have special privileges in their contract that allow for things not usually spelled out on the level they are on.

Level changes. When clients feel they are ready, they can request to move to the next level. Level changes and decisions are discussed in individual sessions and the contract group. Clients must request at the beginning of the group for time to discuss their level-change request. Clients will receive feedback from the staff and peers in the group. The matter is taken by the group leader to the treatment team for a final decision. The client will then be told that same day or the next day whether the level change was approved.

Down leveling. Occasionally clients are moved up to a level and find that it is too difficult to accomplish the tasks on that level. Clients may be down leveled to an appropriate level with more structure until they are ready to try again.

Weight. Unless otherwise contracted, weight is taken and recorded once weekly with bulimics and twice weekly with anorexics, with the client's back to the scale. Only the therapist, the clinical director, or dietitian may tell the client her weight or any changes in weight.

Mealtimes and place. Clients will be asked not to go to the kitchen or begin any meal preparation until scheduled meal or snack time and not without staff present until they are on Level IV or Level III by contract. Clients are to eat meals in the dining room or other area supervised by staff until Level IV.

Snacks. Snacks will be served two or three times per day according to client needs. Protocol for snacks is the same as meals, according to the client's level and contract.

ENTRY LEVEL

The first phase in our level system is the Entry Level. Entry Level begins with the client's admission into the facility and continues until the first contract is made. During this time clients are getting acquainted with our program and will be given an Entry Level contract that lists certain tasks to be accomplished. Assessments will begin right away, and the treatment team will be getting to know the client. During Entry Level, clients are on a "grace" period with no formal requirements for eating. This gives us time to know the client and what her needs will be. In some cases an initial calorie assignment may be made. During Entry Level, clients will attend meals with other clients and a staff member, but no formal eating requirement is made. Entry Level lasts no more than three days. After Entry Level, the client helps develop her first contract on Level I and then continues on through the level system. An example of our Entry Level contract is provided along with our program schedule on pages 273 and 274 at the end of this chapter.

PHASES OF TREATMENT

- Initial interview, clinical assessment

- Comprehensive history and physical by our or your medical doctor

- Admission and orientation to the program

- Comprehensive psychological assessments, including a psychiatric evaluation

- Nutrition/exercise assessments and initial meal and exercise plan established

- Treatment team establishes a treatment plan

- Active involvement begins in therapy, education, activities, and family sessions

- Client works through the level system, gaining understanding, control, and confidence, and establishes a lifelong plan for recovery and wellness

- Staff helps client to make transition through the level system, providing increasing responsibility for self-care

- Treatment team, with client, reevaluates discharge criteria and discharge date

- Discharge with plan for transitional living or other aftercare

TREATMENT COMPONENTS

- Individual, Group, and Family Therapy (Cognitive Behavioral and Psychodynamic Therapies)

- Psychiatric Evaluation and Treatment

- Medical Monitoring

- Communication and Life Skills Training

- Meal Planning, Shopping, and Cooking

- Nutrition Education and Counseling

- Exercise, Fitness, and Rehabilitation Program

- Art Therapy and Other Experiential Therapies

- Occupational, Career Planning

- Biochemical, Nutritional Stabilization

- Body Image Treatment

- Sexuality, Relationships, Co-Dependency

- Recreation and Relaxation

- Education Groups - Topics include: stress, psychological development, self-esteem, compulsive behaviors, sexual abuse, spirituality, anger, assertiveness, relapse, shame, women's issues

TREATMENT OBJECTIVES

Our objective is to help each client achieve a clear understanding of her eating disorder, its effect on her life, and what is necessary for her personal recovery. Our goal is to develop and initiate a plan for recovery that will be able to be maintained on discharge. We assist clients to:

- Eliminate starving, stop binge eating, purging, and compulsive eating

- Establish nutritious, healthy eating patterns

- Get into balance nutritionally, biochemically, and metabolically

- Gain insight into disordered thinking

- Gain insight into the underlying causes of the eating disorder behaviors

- Learn appropriate expression of anxiety regarding food and weight issues

- Work toward achieving an "ideal body weight" within an accepted range

- Gain insight into destructive attitudes and behaviors

- Develop a balanced weight maintenance plan involving food and exercise

- Improve body image

- Use journal writing and self-monitoring

- Discover and utilize alternative coping skills other than the eating disorder or any other self-destructive acts

- Work with their significant others in the development of improved understanding and improved communication in order to break patterns that enable the eating disorder to continue

- Alleviate depression and anxiety and improve self-esteem

- Identify and constructively express emotions and receive support in developing coping strategies for living free of destructive behaviors

- Use independent experiences and therapeutic passes in order to create a lifestyle that can be continued on discharge

- Develop relapse prevention techniques

| Entry Level Contract | ||

| Name __________________________________________ | ||

| Date | Initialed | Dated |

| Orientation to Program by | _____ | _______ |

| Eating Disorder Program Description Read | _____ | _______ |

| Client Handbook Read | _____ | _______ |

| Eating Disorder Inventory and EDSC | _____ | _______ |

| ED Evaluation/Psychosocial by | _____ | _______ |

| Dietary Assessment by | _____ | _______ |

| Diet Recommendations (Energy Units) | _____ | _______ |

| Observations | _____ | _______ |

| Exercise Assessment by | _____ | _______ |

| Initial Exercise Approved by | _____ | _______ |

| History and Physical by Dr. | _____ | _______ |

| Psychiatric Evaluation by Dr. | _____ | _______ |

| Other Initial Goals/Comments | _____ | _______ |

In coming to Monte Nido I have agreed to begin a new journey toward wellness so that I can fully participate in life on earth. I realize that for this journey I will need a vehicle, a body. In order to have a healthy body, I will need to feed it with appropriate foods. While I'm learning to do this I may stumble along the way, as it is human to do so; but I will forgive myself and I will give myself permission to ask for assistance, guidance, and support. My goal is to abstain from intentionally harming or neglecting my body. I realize that this will be essential in completing my journey to eating disorder recovery. I will strive to make my relationship with my body one of forgiveness for its imperfections and one of honor for its value. I realize that all of this will be a difficult task. I agree to go forward with these goals and have come to Monte Nido because I have been unable to accomplish them on my own. There will be times when I am afraid, I do not understand, or I do not trust those trying to help me. Nevertheless, since I believe I can find the help I need at Monte Nido, I will be honest, I will listen to the wisdom of those who have already completed the journey and recovered, and I will face my fear with them at my side.

I acknowledge that if I am unable to participate in the program at Monte Nido, I could be jeopardizing my health and therefore may need to transfer to a facility where more structure and medical care are available.

| Client's Signature | Clinical Director |

| _____________________ | _____________________ |

* Individual Assignments = clients working on assignments

** Independent Cooking - dinner without Louise

next: Nutrition Intervention in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS)

~ eating disorders library

~ all articles on eating disorders

APA Reference

Tracy, N.

(2008, December 17). Eating Disorders: When Outpatient Treatment Is Not Enough, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, April 15 from https://www.healthyplace.com/eating-disorders/articles/eating-disorders-when-outpatient-treatment-is-not-enough