Managing medical issues with dissociative disorders can include reducing stress at a doctor's office. Doctors and hospitals can be stressful and anxiety-provoking, which can increase dissociation. For some, medical issues can even be a trigger of past trauma. So what can you do to stay healthy, manage medical issues and reduce stress at a doctor's office with a dissociative disorder?

Support for DID

People with dissociative identity disorder (DID) often experience recurring grief. This grief is not always connected to physical loss and death. It can also be connected to symbolic loss, a type of loss commonly experienced by trauma survivors. This type of loss can have profound, lasting effects. For a person with DID experiencing grief because of symbolic loss, the entire system can be affected, complicating the grieving process even more.

For many people around the world, December is a month of celebration, with numerous holidays taking place throughout the last month of the year, but managing the holidays with dissociative identity disorder can be tricky. The holidays can be joyous and exciting for those who celebrate. For many with dissociative identity disorder (DID), however, this time of the year can be tremendously stressful and anxiety-provoking. Dissociative symptoms can worsen during the holidays, but there are steps you can take to make managing the holidays with DID a little easier.

When my brother was little, he went to school one day, climbed on top of his desk, and screamed. He didn't say anything. He just screamed. Nobody asked him why. When he ran away from home a few years later, the pastor of our church came over, witnessed my father's performance as a remorseful parent, and didn't concern himself with what exactly my father had to feel so regretful about. When I was six, my mother took me to a doctor – one of my father's colleagues – who asked her what had happened to make me bleed. I don't remember what she told him. All I know is that it wasn't the truth. She didn't know the truth. Only I and my father did. And no one asked me. Of course, by then I already had dissociative identity disorder (DID). Who knows what I would've said if they'd asked.

Of all my Dissociative Living posts, only one was written for partners of people with dissociative identity disorder (DID). Maybe that's why the emails I still receive now and again from readers are almost always from partners. And the emails are always the same: something like, “I love my partner, but someone in their system broke up with me/told me to go away. Other parts love me and want me around. What should I do?” It's uncanny, really, how nearly identical each of these emails are. And here, once and for all, is my response to everyone who finds themselves desperate to know what they can do about their partner with dissociative identity disorder.

Reader Deanna asked if anyone has ever experienced remission from Dissociative Identity Disorder. If we’re defining remission as a period of diminished, unobtrusive dissociative symptoms – “normal” dissociation, in other words – then I’d wager there are people who have experienced exactly that. But they have worked hard to achieve that degree of integration and awareness. It didn’t happen spontaneously, which is what I suspect most of us with Dissociative Identity Disorder mean when we bring up this idea of remission. And I also suspect it isn’t really integration we’re talking about, but the apparent disappearance of other personality states. I’m guessing plenty of people experience this latter scenario too; but remission it is not.

I just finished reading a young adult fiction series called The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins. It’s a dystopian tale, set in an oppressive, violent, and nearly hopeless future. I recommend it solely because it’s a gripping, invigorating read -- but, as someone with both dissociative identity disorder (DID) and PTSD, there’s something special about The Hunger Games that impresses me: its remarkably deft portrayal of the immediate and long-term effects of trauma.

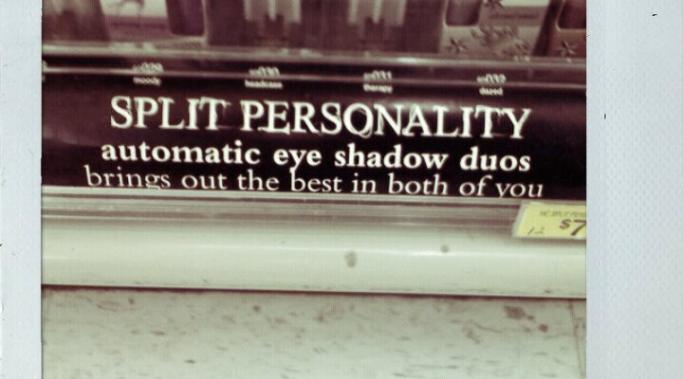

Yesterday, I came across a picture of a sign I’d taken several months ago while out shopping. The sign was under a display of eye shadow applicators that each contained two different colors and it read, “Split Personality – brings out the best in both of you.” Two shades of make-up, one for each personality. I’m sure someone fancied themselves terribly clever when they came up with that. But as much as I loathe the idea of suiting up with the PC police, I have to say that glamorizing Dissociative Identity Disorder to sell beauty products isn’t at all clever. In fact, I think that the pervasive use of mental illnesses as punch lines undermines efforts to promote understanding and support for people living with them.

Decreasing dissociation in dissociative identity disorder (DID) relies on actively increasing awareness of the world around us. Dissociation is the process by which we separate ourselves from our experiences, memories, bodies, and very selves. When we're dissociating, we're disengaged from some or all of our own reality.

It's not inherently a bad thing; I truly believe dissociation serves a valuable purpose, and not just in traumatic circumstances. But there's no doubt that the chronic, severe dissociation intrinsic to dissociative identity disorder is problematic, disruptive, even at times actively destructive. By increasing awareness, by being more fully present in our bodies and minds, we can mitigate the damaging effects of dissociation.

How many times have those of you with Dissociative Identity Disorder drawn a boundary of some kind and later felt awash in guilt and anxiety? If you're like me, the answer is "just slightly less than always." And it's not just those of us with DID that struggle with boundary setting. That backlash of guilt and anxiety isn't unique to Dissociative Identity Disorder. But I suspect the path to resolving it might be.