Bob M: Good evening everyone. The conference topic tonight is: "Coming Out. Sharing the news of your eating disorder with significant others in your life." We'll also be discussing other aspects of recovery. Our guest, Monika Ostroff, details her 10-year battle with anorexia in a new book Anorexia Nervosa: A Guide to Recovery. Welcome to the Concerned Counseling website Monika. So our audience can get a sense of what you went through, please tell us a bit about yourself and what qualified you to write a book on recovery.

Monika Ostroff: Good evening everyone. Thank you for inviting me tonight. I struggled with anorexia for about 10 years. I spent approximately 5 years in-and-out of hospitals, mostly in. Recovery for me entailed a lot of soul searching and trial and error. When I finally found some things that worked for me...after such a long time of no luck...I thought it would be important to publish a book. I thought that some of the things that were helpful to me were bound to help others.

Bob M: How old were you when your eating disorder started and how old are you now?

Monika Ostroff: I had "disordered eating" when I was about 18, a little older than most. I'm 31 now. It started innocently enough. After gaining the official "freshman fifteen" in college, I decided that I needed to lose the weight and "get my old body back". My diet ended up being a little extreme and lengthy.

Bob M: Many of the visitors to our site and our conferences always talk about how difficult it is to tell others about their eating disorder (anorexia, bulimia, compulsive overeating) and their need for help. Can you tell us how it was for you?

Monika Ostroff: I spent about four years denying that I even had an eating disorder. To tell you the truth, initially, I don't think I told anyone. Pretty much everyone could look at me and figure it out on their own. When I went into the hospital for my first tube feed, I had to tell some of my friends whom I hadn't seen in awhile. I remember feeling afraid and ashamed. Part of me was afraid that people would look at me differently and that they would watch me more closely, at least in terms of what I ate. Another part of me was embarrassed to have ended up in such bad shape.

Bob M: Did you ever regret not being able to tell someone before it got to the point that you had to be hospitalized?

Monika Ostroff: I haven't ever really regretted it per se. I do wish that I had been able to find a compassionate therapist to work with sooner. It would have been nice to have spared myself some time in the hospital. And I do know that the sooner you catch it and work on it, the smoother your recovery goes.

Bob M: For those just coming into the room, welcome. I'm Bob McMillan, the moderator. Our guest is Monika Ostroff, author of Anorexia Nervosa: A Guide to Recovery. We are talking about sharing the news of your eating disorder with significant others, how to do it, and why. We'll also be discussing eating disorders recovery a bit later. Here are some audience questions Monika:

Gage: What happened to make Monika enter the hospital? How long had she gone without eating and what symptoms did she have?

Monika Ostroff: I had dropped down to the low 80/high 70-pound range. I was weak, shaky, and had begun passing out, particularly when trying to walk up the stairs. At the time, I was eating only a couple hundred calories a day and I would purge anything over that so my potassium level was frighteningly low. I was also in the midst of law school exams and unable to think very clearly. All of that, coupled with a trip to the doctor, sent me to the hospital.

Reni62: Why didn't you stop when you got to your weight goal?

Monika Ostroff: Aaah yes, well...the weight that I wanted kept changing. First it was 105, then 100, then 98, then 97, and so on. Nothing was ever low enough and I was never satisfied with my goal. As soon as I reached it, I set another one.

Violette: How exactly did you tell your family members about your eating disorder?

Monika Ostroff: Well, my mother had been "nagging" me about food for a while. I think I was finally just scared enough to say "I think I have a problem and I want to do something about it."

Bob M: How would you suggest "coming out" to your parents if you are a teenager or a bit older and telling them about your eating disorder?

Monika Ostroff: I would suggest a step before the actual "coming out" and that is a little fear reduction exercise. I think a lot of people are afraid that once they tell someone that that person will then try to make them do things that they are not ready, or even willing, to do. Fear reduction then, would consist of telling ones self that you are asking someone for support which is different from asking someone to "fix it" for you. The most important aspect of this is realizing that we have to teach others how to support us by communicating clearly what it is that we need. We are asking them to walk with us in recovery...not for us. With that in mind, I would approach the family member or friend I trust the most and say "I have something really important that I would like to talk to you about, and this is hard for me..." I don't think that it's necessary to go into a blow-by-blow account of symptoms unless the person would like to. But once the person says, "I'm having trouble around food and my weight," I think it should be followed by a request for support.

Bob M: Many parents don't really know if their child has an eating disorder or not and people with eating disorders are very good at hiding it for quite some time. So it's also important to expect that when you tell a parent or significant other, that they may express surprise, shock, worry, maybe even some anger or extreme concern. If you are going to give someone "the news," be prepared for those reactions too. And then, remember to also reassure them and tell them explicitly that you are asking for their support and professional help. Here are more audience questions:

Ack: How did you get others to understand?

Tayler: How did you friends react?

Monika Ostroff: Getting others to understand was never easy, and to be honest with you, some people never understood and still don't. Whenever I found a particularly good article or book excerpt, I tried to photocopy it and give it to people and that seemed to help a lot. I also tried to get people to go to panels of recovered people speaking. That was maybe the most helpful. My friends...I lost a few over it. I suppose they were never really true friends. Other friends were concerned and wanted to be helpful, but didn't really know how; so I had to sort of show them how to be supportive.

Lulu Bell: I am 17 and I've been bulimic for about 4 years. There is only one person who knows. The person that I need to tell, but is the most difficult to tell, is my parents. How do you go about that? My parents have already been through a lot with me like date rape, drug addiction, and alcoholism. I don't know how they would be able to handle this too. Plus it costs a lot to go to therapy and I've been in and out of it for about 3 years. I'm just lost. How should I go about it?

Monika Ostroff: With the history that you've briefly described, it isn't surprising that you are struggling with bulimia. I think sitting down with your parents for a true heart-to-heart would be perhaps the best thing. Sometimes doing that armed with some information in the form of books and articles can help. And as Bob said earlier, reassuring them will be helpful too. I think that the human spirit is very strong and very resilient. You have been struggling with this almost all alone for a long time. They will be able to handle it with you and you can all help each other...beginning with open lines of communication that travel both ways.

Mary121: I was wondering if you're considered overweight, but you had bulimia and anorexia symptoms, would it be a good idea to tell someone?

Monika Ostroff: It's a good idea to get support from another person whenever you are struggling with issues that are difficult for you. The number on the scale isn't really what defines the eating disorder. Eating disorders are mosaics made up of all different kinds of things. It sounds like you might be worried that they will doubt you or look at you critically. I think that if you try to make a connection with people, or a person in particular, and you are saying "I'm struggling, I'm hurting," then that person's heart will respond to your heart with support. Be willing to educate people along the way of your journey. That is how we all change and grow.

Bob M: Our guest is Monika Ostroff, author of Anorexia Nervosa: A Guide to Recovery. I'm getting some questions about where to purchase the book. You can click on this book link: Anorexia Nervosa: A Guide to Recovery ($11.00) and it will open a separate browser and you can get the book and still stay tuned to the conference or check your local bookstore. Here's an audience comment:

Crickets: My daughter got a lot of help through counselors when she entered college. It was a good turning point for her

blahblah: I'd like to ask Monika how she worded her "confession" to loved ones. I mean, part of me wants to be "discovered", but I can't imagine saying, "hey, pay attention to me! I'm starving myself!"

Monika Ostroff: Well, our behaviors do sort of say , "hey, pay attention to me," don't they? I like the way you worded that. I really didn't have a whole lot of finesse when I told some people. I think I literally said, "I have an eating disorder." I had to take into account people's personalities. My father is the sort of "give it to me straight" kind of person. He's the one that got the "I have an eating disorder." My mother needs a little more padding. She was the one that got the "you know, I've been thinking a lot about things that I do. I know that they aren't 'normal' and I also know that I can't stop doing certain things. I think I may have a problem with food and my obsessions with weight and exercise."

Bob M: And how did they react to those statements?

Monika Ostroff: My father said something like, "you have a what?! Just go out and get yourself a pizza." My mother on the other hand began talking about the problems in her life at the time. That's just where she was back then. Of course, neither one of those reactions was terribly helpful and hence I lost more weight, got into medical trouble and ended up in the hospital. Not the brightest story, but one I can look back on and use as a marker for how much we have all grown and changed since those days.

Bob M: I want to move onto your recovery. What was the turning point for you?

Monika Ostroff: The literal turning point came with a memory. I was in the hospital for what seemed like my millionth admission, when suddenly I remembered days in high school when I'd had a lot of friends, a lot of respect, and most importantly hopes and dreams for a future. All of that seemed to be gone. I was terribly depressed, had finished a series of ECTs, and somehow had developed an identity as a patient. It was an identity I didn't want. I began to realize that I treated myself harshly, and that the programs that didn't work for me also treated me harshly and pretty rigidly, too. I'd been treated that way a lot in life, and somewhere deep inside was a soft voice begging for comfort, gentleness, and understanding. I managed to find, after a 4 hour admission to a program that was not very user friendly, a program based on the feminist relational model, emphasizing respect, compassion and connection to others. It was really there that the true seeds were planted.

Bob M: Just so everyone in the audience understands, what do you mean by the word "recovery"?

Monika Ostroff: For me, and I'm very clear about this within myself, for me recovery means being back to the way I was before I even knew what a calorie was. I am normal weight, eat three meals a day and I snack when I'm hungry. I don't avoid any food in particular. Well, except for lamb, but I just can't stand the taste. Other than that I eat everything and I eat without fear, without anxiety, without guilt, without shame. For me, that 's recovery.

Bob M: How long did it take to get to that point?

Monika Ostroff: Well recovery was a process of both discovery and healing. I think that I learned a lot in every program I was in. Even hurtful times were educational. The last program I was in lasted about 9 months and that was the true beginning point for me. After my discharge from the program, I worked on my own, very hard I have to add, for about another 5 months and each day symptoms and fears lessened. I used markers. I remember leaving the program the day before Thanksgiving. Two days after Thanksgiving was the last day I purged or starved. I started counting months of health.

Bob M: Here's an audience comment on your definition of recovery that I'd like you to respond to Monika:

Sunflower22: That seems so farfetched!

Monika Ostroff: I think that it sounds farfetched only if you have been told that "true" recovery is out of reach, only if you've been told that "once you have an eating disorder, you'll always have an eating disorder and that all you have to hope for is that one day it will all be a little more in perspective." Those kinds of things become self-fulfilling prophecies. And those definitions of recovery were not what I wanted for myself. I did not want to always feel tortured. So getting back to how I was was important for me. What you believe. you can become. What you wish for, you can reach. Your inner power is most amazing once you tap into it and follow it.

Bob M: Here are other similar comments, then a question:

Tammy: Monika, do you think that complete recovery is possible? I mean it just seems so hard to believe that I could get to the point where I didn't know what a calorie was or care.

Ack: That is all I have ever heard, that you will always have it.

Dbean: Do you struggle with going back and forth between wanting to get better and wanting to keep the eating disorder?

Monika Ostroff: To respond to the first question: I do honestly believe that complete recovery is possible. Getting there requires some very hard work, a lot of introspection, asking some really tough questions and then going out and really digging for the answers. It is almost invariably connected to discovering and validating your self-worth. When you feel worthless, it's hard to imagine even doing that but it can happen... with time, with patience, with persistence. Going back and forth between an eating disorder and getting better happened in the beginning and in the middle of my recovery. I think that ambivalence is a normal part of recovery. After all, look at all the important things eating disorders can do do for you. They protect you, communicate for you, manage your feelings. The thought of living without one is scary at first. It's like learning to navigate the world in a new ship. But new ships, I have found, can sail a whole lot better than old ones. You learn to make connections, to fill the space your eating disorder filled with people. I think we all deserve the life-affirming connections of healthy relationships. Those relationships can only exist and unfold when we stop befriending anorexia and bulimia and make them move aside. It takes time, it's a process a journey. One well worth the effort.

Bob M: Earlier you mentioned that you attended several treatment programs. How many? Why did you have to do that? And how long was it from the time you started your first program to the point when you said to yourself "I'm recovered"?

Monika Ostroff: Four-and-a-half years, perhaps five, since the start of the first program to the recovered point. I was hospitalized in eating disorder programs and non-eating disorder programs and I'm not sure what the grand total is. Several programs, I was in more than once. I know that there was one year in particular when I was only home for a total of 2 weeks. I was searching for the answer and I was pretty determined to keep searching until I found it...within the limits of my insurance policy, of course.

Bob M: Just to clarify here, are you saying you went from one eating disorder treatment program to another in search of the right one for you? Or was it that you were able to control your eating disordered behaviors for awhile and then you relapsed?

Monika Ostroff: Nine different programs total. I finally did the math. After my first admission, I managed to stay out from July to February, then I went in for a month. Then I was discharged and stayed home until June and then I was inpatient literally all summer. I stayed out two months and went back in. Literally, in and out. I was "barely managing," I'd say. Particularly the year I was just plain old "in the hospital." The treatment part isn't well detailed in the book, but that is pretty much how it goes.

Bob M: Why did it take you five years to recover?

Monika Ostroff: Many reasons, I think. I took me that long to figure out that what I really needed was gentleness and compassion. I had a lot of clinicians give up on me, and the one person who was right there with me, well, her voice was pretty much drowned out by all the clinicians who said "you'll always be this way". It took me a long time to dare to say that I wanted to search for the shreds of worth within me and work towards a healthier life for myself. It took me that long to figure out that to get better I had to like and love myself as much as I liked and loved my friends. To do that I had to learn to listen to and heed the voice in my heart while developing my own authentic voice to express my needs, desires, pain, and dreams. All of that just takes time to cultivate. There is a lot of searching within yourself, a lot of questions to be asked and answered. It took me some time to figure out that sometimes not having an answer was an answer in and of itself. For example, "Why do I not deserve anything?" "How am I different from others?" I always felt different, but I could not define how in specific terms outside of the fact it was a feeling I held within myself. I was bad, different. Why? Couldn't say specifically. I started considering that perhaps I was not all that different, perhaps I did deserve something, perhaps bad things had happened to me by chance and not because I deserved them. All that takes awhile to realize, I guess.

Bob M:Here are some points to remember then: It's important to reach out to others and ask for help and support. That is an important part and you need people who care about you to be there throughout the recovery process. Secondly, it takes a lot of hard work. It's more than just walking into a treatment program and saying to the docs "fix me". And, as many of our previous guests have said, you may have relapses along the way. Don't give up. Deal with them early and work hard to move past them. We have some audience questions focusing on the medical aspects of your eating disorder Monika:

Gage: I am an older woman and have been suffering with anorexia for years. I know this eating disorder is hard on the heart. I do not want to die, but I also feel I cannot win this fight. Will there be a warning when my heart has had enough?

Monika Ostroff: For some people there are warnings, but for many people there are no warnings at all. In that respect, eating disorders can be like playing Russian Roulette. They are dangerous, life-threatening. Keep struggling, striving, and choosing life. We're all with you in spirit. I believe in you!

Bob M: Gage, I want to add, we are not doctors, but many medical experts have appeared here and stated: you can simply drop dead from your eating disorder without much warning. So I hope you will consult with your doctor. Watch for shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, sudden sweating, nausea.

Diana9904: Did your body bloat and expand? When does that start to normalize and is there anything you can do to help alleviate it some? It's real hard to make yourself eat normal when you can see yourself expanding.

Monika Ostroff: I definitely experienced bloating and "expanding". My eating disorder gave me some long-lasting gastrointestinal motility problems which contributed to the bloat. The worst of it took about 5 months to pass. I tried to drink as much as possible and I made sure to wear loose clothing. The best thing I did was tell myself that the only way through this was through....if I purged or starved, and then I was just prolonging agony. I had to go through it at some point since I didn't want to keep my eating disorder forever. My body had just about had it. Somehow reassuring myself that it would end, helped. Also have your doctor or nutritionist reassure you. It really is part of the process and as uncomfortable as it is, it really does pass.

goes: Did you ever feel like you just could not fight the fight anymore and just could not see any light at the end of the tunnel?

Monika Ostroff: Yeah, I felt that way about 3000 times, at least. And I think I had a period of more than a year that I was sure that I was living at the bottom of some deep black pit; but somewhere along the way I started to realize that hope wasn't always this intense feeling. I had to search, sometimes, for evidence of hope in what I did. When you are feeling particularly hopeless, look at the fact that you are keeping your doctors' appointments, your therapy appointments, that you are reading and searching for answers. The fact that you are here with us tonight is evidence that somewhere inside yourself is the light of hope. It will grow. Sometimes even finding someone who is recovered to just sit and talk can do wonders for rekindling hope.

Bob M: The other people with eating disorders that you interviewed in your book, did you get a sense from them that eating disorders recovery was extremely difficult to reach, or was it a lot easier for some than others?

Monika Ostroff: It really varied. Some people went into a program and worked in recovery for a year and did fine, others had roller coaster courses and were in and out of the hospital. There are people that I was in treatment with who are still struggling. It is/was very varied.

Bob M: Did most have to go through a treatment program to recover, or were there many who engaged in some sort of self-help?

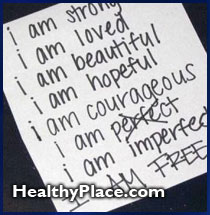

Monika Ostroff: Pretty much everyone had been in some kind of treatment, whether that was individual therapy, group therapy, day programs, inpatient programs varied widely among people. Most people did say, however, that the most important aspect in their recovery was learning how to respect and care about themselves, and a lot of that work was done through journals and positive self-talk. A combination of self-help and treatment seemed to be the most popular combination.

Bob M: We have some questions relating back to the early part of the conference about "coming out" and sharing the news of your eating disorder with your parents, friends, spouses, significant others.

eLCi25:What advice can you give to family and friends of an anorexic who is well aware of her problem (even gives sound advice to other anorexics on how to achieve a successful recovery) but doesn't seem to be ready or willing to get better herself?

Monika Ostroff: I would strongly encourage them to model for her. By treating her with consistent compassion and respect she will learn to integrate compassion and respect into herself. At the same time, I think it is important for the family to be clear within themselves and with her about what their limits are. For example, how much time can they devote to talking in depth with her? Set that time and commit to it, don't overextend. Are they willing to buy special food for her or not? What I'm trying to say is that we all have limits that we must respect and honor or we won't do anyone any good. I think a big part of that is also being honest and open in communication. Talking honestly and lovingly about what they see and what they are worried about. Hopefully she will be able to hear their concerns and will be able to communicate with them about what her fears are or may be.

Tinkerbelle: I am recovering from anorexia. I have always been ashamed of actually admitting my problem, even to my helpers, because I feel they view it as a weakness. Am I delaying the recovery process?

Monika Ostroff: Tinkerbelle, what you say reminds me a little of myself. I can identify with that feeling of thinking that helpers view it as a weakness or flaw, something we should be ashamed of. In reality, however they do not. I don't think that you intend to delay the recovery process purposefully, but that is the effect your silence is having right now. I think it would be an enormous step to tell your treaters just exactly what you said here tonight. It will feel scary, embarrassing, and intensely uncomfortable. Sit with those feelings, bear them. You will be amazed at how quickly they pass in the presence of your helpers' compassionate response. You will also be surprised at how much strength you will glean from doing this. It takes warrior spirit and a lot of courage to do it. It's within you, you can do it. You deserve to have a companion along the road to your recovery.

Britany: I've recently been diagnosed with an eating disorder, but I'm overweight. Why are they so concerned? I'm 5'6". As of three weeks ago, I weighed 185. Now I weigh 165. So I'm still like 35 pounds overweight. Why should I be concerned over weight loss with this? I don't want to eat because if I do I'm afraid I'm losing the only control I have over my life. I'm afraid to eat because I really don't know how to eat properly. I know it sounds silly but...

Monika Ostroff: It doesn't sound silly at all. No matter what anyone's weight is, rapid weight loss and purging habits are dangerous and life-threatening. Working closely with a nutritionist to develop a meal plan that is acceptable and tolerable to you may be tremendously comforting. I do mean working WITH a nutritionist, you have a say in your recovery and what happens to you. Control is such a huge issue, a very important, very sensitive issue. But the way I've learned or come to look at it is--can you stop doing what you are doing with food right now? Even for one week straight? If the answer is no, you're not in control, your eating disorder is. It doesn't take long to be chained in behaviors and ways of thinking that are rigid and soon out of our control. You deserve to be free, you deserve a full life, one much fuller than the life anorexia and bulimia can ever offer you.

Bob M: And as many visitors to our site can tell you Britany, their anorexia or bulimia started with a diet. So please be aware of that and be careful.

Yolospat: I have an eating disorder, but it's just the opposite. I weigh 220 pounds, but I still have all the same feelings like the eating disorder is taking over my life. Could a program similar to yours help me?

Monika Ostroff: Absolutely. No matter what the scale reads, the process of cultivating your own unique voice, learning to listen to your heart and be gentle with yourself and your needs is the same for everyone. Learning moderation and acceptance is something that no scale can teach or define.

Jelor:Coming out seems more difficult when you are an adult and no longer with your parents. What can a person do to force them to tell people and ask for help. There aren't friends who are close. The family knows, but does not want to be involved.

Monika Ostroff:Coming out can be more difficult as an adult if you feel that there is no one there to support you, be it friends or family members. I think that attending panels of recovered people speaking and attending eating disorders support groups can be tremendously beneficial at this time. Regarding forcing someone to divulge they have an eating disorder, no, you can't force anyone to come out. That is an individual choice for the person to make on his or her own. The person may not be ready to come out yet, and that is something to consider as well.

Jelor: I'm 36 years old and was diagnosed at 30. I want to be healthy and to get well but I won't tell people or ask for help. My parents have refused. I don't really have close friends here to speak of, just coworkers.

Bob M: Jelor, I would suggest joining a local support group in your community. That way you can feel a bit more comfortable talking with others who have similar issues and hopefully that will encourage you to seek professional treatment for eating disorders.

Monika Ostroff: I also think that it is worth exploring why you refuse to ask for help. Are you afraid that people will not be there for you? That you will get better before you are ready to get better? Just some thoughts to explore.

Bob M: Also remember, recovery isn't meant to please other people. It's for YOU! So YOU can live a healthier, happier, fuller life.

xMagentax:A few people have told me I have an eating disorder, but I've only made myself sick a couple of times. I don't how to tell if I have an eating disorder or not.

Monika Ostroff: Are you preoccupied by thoughts of food and weight? Do you weigh yourself more than once a day? Will you refuse to eat certain foods because they are "bad"? Will you exercise even if you are sick or the weather is beyond bad? Do you feel anxious around food? Do you have trouble eating in front of others? These are just some other signs of an eating disorder. If food and weight take up the majority of your thoughts, chances are an eating disorder is on its way in- if it's not there already.

Debbie: My town is small enough that it doesn't have any support groups. What else do you suggest?

Monika Ostroff: Local colleges in surrounding towns often offer support groups. Many high schools also offer support groups. There are a wealth of resources on the web as well. You can call any of the national eating disorder organizations for referrals, too.

Bob M: Here are a few audience comments about things we've been discussing tonight:

dbean: Every time I go to the doctor, everything seems to be fine. So I continue in my behaviors. I feel exempt from any problems.

Tayler: I agree with Goes. It's too scary to think about recovery. I want to but I feel so completely out of control.

Sunflower22: Loving yourself and learning to cope with life without an eating disorder would be a good thing.

Ack: My boyfriend says, "If you don't like what you see, just go to the gym!" How do you help them to understand?!

Mary121: Yes, I'm really afraid to tell anyone since I haven't gotten "thin enough" yet. I can't let it go.

Candy: I've been through an inpatient treatment center already, and did okay for a couple of months, but I am completely back into my old behaviors and try to hide them from my husband and other family members. I think they know, but how do I talk to them about it, since I am supposed to be "better"?

Monika Ostroff: An honest heart-to-heart talk. Open communication is always the answer. In the process of letting them know how you are doing, you'll need to educate them that sometimes there are slips and relapses along the way. The road to recovery isn't necessarily linear. It's also important to let them know that recovery is a process, not an event. Sometimes it isn't the precise words we use that make the communication easier, it's the fact that it comes from the heart at a time when we are vulnerable; which is scary, I admit. They may not respond in the way you hope, in which case it is perfectly okay for you to tell them that. It's okay to tell them what you had hoped for and what you continue to hope for. That is all part of learning to communicate clearly and effectively. It's also an important part of getting your needs met.

Bob M: I know it is very difficult to admit our problems. There are a lot of issues involved and certainly fear of the unexpected reactions from others plays a big part. But the other side of that is, if you don't tell the people close to you, if they find out on their own, you can expect them to feel very hurt, deceived, even angry. Imagine thinking you are with a certain type of person, then later finding out that the person didn't tell you the whole truth about themselves. And, if it helps, take the "eating disorder" out and substitute alcohol, drugs, a criminal record from the past. If someone didn't tell you about these and you found out on your own, how would you feel? The other part of it is that you want this person to be on your side, to be helpful and supportive. And being communicative and honest is the best way to accomplish that. What is your reaction to that Monika? And if anyone else in the audience would care to comment, please send it to me so I can post it.

Monika Ostroff: Excellent points. It's hard to be "up front" when you're feeling shame and feeling generally bad about yourself. But you would want to know were the tables turned. It's important to remember that people can only be helpful and supportive when they know the truth. It will be hard for you, but you are well worth the effort!

eLCi25: As a parent, I am often confused and even scared at times to talk to my daughter about the eating problem. I try to persuade her to eat and, from my experience living with an anorectic, I know how that sparks her anger, but its an instinctive response to get my child to move toward more healthy living. How do I treat the problem? Should I just not talk about it with her? I feel like a negligent parent if I don't bring it up. (how to support someone with anorexia)

Monika Ostroff: Again I think honesty is important. Ignoring the problem won't make it go away. Gentle, firm, persistence will show that you care about her, her health, and future well-being. Talking about it will inevitably spark anger. Validate the anger with "I hear that you are angry" or "I understand that you are angry." I think avoiding the anger is what gives it so much power. If you can tolerate her anger and she can tolerate yours, then you will both be able to communicate more effectively which in turn will facilitate her recovery. Of course this all takes some time.

Bob M: You told us earlier how your parents reacted to the news of your eating disorder when you initially told them:

Jackie: What did other family members say?

Monika Ostroff: I'm an only child, so my family members are limited. I have other relatives who were like siblings to me since we grew up together and lived very close. They all sort of ignored it for a long time. Then I found out that they were talking about me behind my back, saying things that were not nice, to put it lightly. I didn't get the supportive, concerned routine by any means. Though to be fair, despite my father's not understanding, he was always there to visit me, always there to care in his own way; though I admit to not appreciating his telling me to "just eat" at the time.

Rosebud2110: I told people close to me after 3 years and I got help for about 2. I just got out of the hospital about a month ago and now I am having a really bad relapse; but I am total denial that I am in trouble and I don't want to be in therapy any longer. Should I stop therapy or keep going?

Monika Ostroff: You may have answered your own question. You are able to recognize that you are having a really bad relapse and you recognize being in denial, which I interpret to mean that you are not completely connected to the severity of the situation in your heart, though your mind is able to recognize it. This alone is a fruitful topic for a therapy discussion. I can understand feeling tired, maybe stuck and a whole host of other things, but I also sense some warrior spirit in you and that part would benefit greatly if you were to keep going to therapy. I recommend going and continuing to work toward the full life that you so richly deserve.

Bob M: Two final questions: You said you have "recovered". Since that point, have you ever worried about falling back into old habits? And, if so, what do you do about it?

Monika Ostroff: In the very very beginning of my eating disorder recovery I worried about it because I'd read so much and heard so much about how eating disorders are your Achilles' heel. And I watched all of my thoughts and all of my behaviors in a way that felt disordered! I remember thinking "this is ridiculous!" Literally. I told myself that I was recovered, that I'd learned new ways to navigate through life without my eating disorder and that if I always led with my heart and followed with my head I would be fine because I knew/know that my heart would never tell me to hurt myself in anyway. I have had some intensely stressful times since being recovered and I've never fallen back into my old habits. I do notice that if I'm particularly sad about something, I'm not usually terribly hungry; but at those times, I'm also very clear within myself that it is not about food, it's about sadness. I guess that is my way of saying that I am mindful.

Bob M: By the way, do you have any lingering medical problems as a result of your eating disorder?

Monika Ostroff: Unfortunately yes. Nothing terribly serious, just incredibly annoying at times. For whatever reason, it is taking my gastrointestinal tract a very long time to regulate. I had to take a motility agent for 3 years which then gave me heart problems. I had to stop taking it. It's not the worst thing in the world and it seems to be getting better. Compared to 5 years ago, it's great! The only other thing I notice is that when I have the flu (only once in 5 years) it's pretty easy for my potassium level to drop, easier than it was before I'd had an eating disorder. That's about it for medical stuff for me. I think I'm pretty lucky in that regard.

Bob M: What would you say are the biggest differences in your life, comparing life with, and without, the anorexia? Besides the obvious health implication, why would anyone want to give up their eating disorder?

Monika Ostroff: There are lots of reasons to give up an eating disorder (eating disorder information). An eating disorder makes it impossible for you to fully connect with another person in a relationship. The eating disorder is like a glass wall, a barrier that stands between you and the other person. And while that can be protective (if you've been terribly hurt before), it can also be hurtful in that it prevents you from having people really enter into your experience with you to celebrate your triumphs, comfort your pain, and cheer you on in your efforts to reach your dreams. The eating disorder tends to color true emotions. I feel so much more vibrant without anorexia. My emotions are clearly defined, my relationships are deep and meaningful. I am much more in tune to myself and my needs. I think my marriage has benefited enormously since my recovery. My husband and I got to fall in love all over again. When I recovered, I was, for all practical purposes, a new person. And you have so much more energy!!! All that energy that goes into starving, worrying, purging, exercising, when you rechannel that it's absolutely amazing what you can accomplish!!

Bob M: Monika joined us two-and-a-half hours ago and I want to thank her for staying late tonight and answering so many questions. We had about 180 people visit the conference tonight. You've been a wonderful guest and had lot's of good insights and knowledge to share with us. We appreciate it. I also want to thank everyone in the audience for coming tonight. I hope you found it helpful.

Monika Ostroff: Thank you for inviting me tonight! Good night everyone.

Bob M: Monika's book: Anorexia Nervosa: A Guide to Recovery. Here's her description of what the book contains: "Coming from a strengths-based perspective, it is meant to be a compassionate, understanding companion on the journey through recovery from anorexia. It offers a combination of factual information, my own story of abuse and recovery from a ten year battle with anorexia, insights from others who have recovered, practical suggestions for recovery and staying committed, a special section for loved ones, and much more." Thanks again Monika and have a good night everyone. I hope you found tonight's conference helpful and inspiring.

Bob M: Good Night everyone.