Concerns for Our Bipolar Children

CABF policy director on the importance of properly diagnosing bipolar disorder in children and the antidepressants-suicide controversy.

Comments by CABF Research Policy Director, Martha Hellander at American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Town Meeting, Washington, DC. (AACAP 2004 Annual Meeting)

Hello, and thank you for inviting me today. I should start by saying that I have no conflicts of interest other than being a mom. I am also the Research Policy Director and co-founder of the Child & Adolescent Bipolar Foundation, a nonprofit advocacy group of nearly 25,000 families raising children diagnosed with, or at risk for, bipolar disorder. Over half of our children are under the age of 12, more than half of them have been hospitalized anywhere from 1 to 10 times, and about a third of them take antidepressants along with mood stabilizers. Many of our members reported in an informal poll last January, as we testified before the FDA, that their children had been suicidal from a very young age, often before taking any medications; others were never observed by their parents to be suicidal until soon after taking antidepressants, and among those families, about half report that the suicidal behavior stopped when the medication was removed.

CABF does not take a position on whether individual cases were or were not caused by antidepressants. Our position is that mood disorders in children are a major public health crisis, and antidepressants are an essential part of treatment for SOME, but not all, of those kids. CABF welcomes the FDA attention, and increased warnings, being added to the labeling of these medications. As we say at CABF, these are powerful and potentially dangerous drugs that are used of necessity to treat powerful and extremely dangerous illnesses.

Doctors and parents must keep in mind that symptoms of depression in a child may not be a one-time episode, but a manifestation of a developmental stage of a lifelong, hereditary illness such as bipolar disorder in which more time is typically spent depressed than manic or schizophrenia. Parents need to know that depression is often the first sign of bipolar disorder, and is also the most common symptom seen in adolescents during the five years prior to the first psychotic break in schizophrenia. So how can we tell which kid presenting with depression is likely to respond well, or have an adverse reaction to, a particular medication? We can't at this time. We can recognize depression in even preschoolers now, but we don't yet know how to match up which kids with which treatments.

To parents demanding an answer, and God knows how badly we want answers, you must stand firm and say "I don't know." We need you to be honest and tell us frankly that if you conclude that our children are depressed, you have no way of telling whether it is the type of depression likely to respond to an antidepressant, or to psychotherapy, or whether the medication might provoke the child to become manic, or go into a mixed state (which is the highest period of risk for suicide in those with bipolar disorder). And until we have a major federal investment into research on these questions, you will have no answers. To quote the Dali Lama, "Wisdom is the ability to tolerate ambiguity." In other words, don't give us false assurances.

To parents demanding an answer, and God knows how badly we want answers, you must stand firm and say "I don't know." We need you to be honest and tell us frankly that if you conclude that our children are depressed, you have no way of telling whether it is the type of depression likely to respond to an antidepressant, or to psychotherapy, or whether the medication might provoke the child to become manic, or go into a mixed state (which is the highest period of risk for suicide in those with bipolar disorder). And until we have a major federal investment into research on these questions, you will have no answers. To quote the Dali Lama, "Wisdom is the ability to tolerate ambiguity." In other words, don't give us false assurances.

Many parents aren't going to like this ambiguity, of course. They want you to reassure them that it is probably nothing serious, that you're confident the child will grow out of it, and they will look back in a couple of years and laugh at how worried they are now. Please do not sugar-coat the implications of depression in a child. You must deliver the bad news, unvarnished, and lay out the worst case scenario, as well as the best case scenario, and admit to parents that you don't know whether this or that treatment will help the child. It is essential that parents hear from you, and from advocacy groups such as CABF, that suicide is a possible outcome of depression itself in children. This fact is not widely known, and until it is, the public will continue to assume that suicides that occur while a patient is on antidepressants were caused by the drug. Large clinical trials were not designed to tell, in individual cases, what happened. Large group statistics do not identify the lives lost, or the lives saved, at an individual level.

Screen the child for mania. Use the Young Mania Rating Scale - Parent Version on our web site; a group led by Mani Pavuluri is presenting a child mania rating scale at this conference on Saturday afternoon. CABF will encourage parents to do this screening at home, so you may find parents coming in more educated than before. This is good. Parents ignorant of the symptoms of mania will not call manic behaviors to your attention unless you ask; we tend to be proud of our young kids who stay up late writing poetry, or plays, or making art projects, and admire their bravery and adventuresome nature as they climb to the top of the tallest tree or go fearlessly headfirst down the slide over and over again. We are not likely to mention that our kids rarely sleep at night, or won't stop talking from morning until night, unless you ask us.

Take a family history. You may discover that this child's family, on both sides, has many individuals with bipolar illness or schizophrenia. Educate parents as to why it might make sense to starting a depressed child with some manic tendencies and a family history of bipolar disorder on one of the mood stabilizers known to reduce the risk of suicide, such as lithium, before starting the child on an antidepressant.

Monitoring. This is the latest intervention to prevent suicide by children on antidepressants that has taken the country by storm - it is called "monitoring." Is there evidence about how effective it is, of what it consists? In what environment? Is the concept of monitoring likely to induce a false sense of security?

I have asked several parents whose children took their lives what sort of "monitoring" might have saved them. I was told about the teenage boy just out of the hospital whose parents pleaded with the doctor and insurance company to keep him over the weekend. He was started on medication, discharged over their objections, and told by the doctor to just "go home and have a low-key weekend" and report for day hospital on Monday. They made it through Friday night, and Saturday, and Saturday night, one or the other of them always by his side, even sleeping with him at night. Come Sunday, the father had to run an errand, and the mother needed to use the bathroom. During a few moments alone, the boy stole the car keys and the car, disabled the family phone, and drove off to end his life. Does this mean that during monitoring, parents should not leave the house to buy food, or go to the bathroom? And how many adults must be present; what options are there for single parents, or with other young children to care for, or working parents?

Another mom told me that her daughter got into the medicine cabinet in the family bathroom, and took all the aspirin and Tylenol she could find. The doctor treating her child had not told her to "suicide proof" the house, had not, in fact, told her at all that a depressed child may attempt suicide. Had she known, she told me, she would have locked up the medicine cabinet. Must the house be "suicide-proofed?" I question whether this is even possible, unless one puts grates over windows, removes closet rods and belts, and locks the doors with deadbolt locks from the inside.

Other parents have told me of how in a moment when their back was turned, their depressed children took kitchen knives and cut their wrists, or got up in the middle of the night when the parents were sleeping, wandering the house to find objects with which to injure themselves. During monitoring, are parents to stay awake round-the-clock? Perhaps "monitoring," to be adequate, means constant supervision, literally round the clock, in a secure environment (so the child cannot run off and head for the railroad tracks to throw himself in front of a train, as one boy did), and in which the cupboards, drawers, utensils, doorknobs, indeed, any object, substance, or opportunity by which to harm themselves or attempt suicide has been removed. I don't know of any such place, except for a locked inpatient hospital unit or locked residential treatment center. What are the implications of that, when insurance companies refuse to cover hospital or residential treatment for so-called "mental" illnesses beyond a few days, and even there, hospitals often use one-on-one continuous observation or check patients every 15 minutes, with round-the-clock staffing. So there is a huge need for some guidance to parents of what exactly does "monitoring" mean for them, and we question whether it is really possible for most families to do it at home.

I want to thank each of you for devoting your careers to studying and healing a particularly painful type of suffering endured by too many children. As times change and we learn more about the brain and how it is molded both by genes and environment, we look to you to identify the illness that is attacking their brains and destroying their will to live and sometimes ending their lives. We look to you to provide healing treatment and advice to help us return them to a normal path of development. It seems ironic that at a time when your services are in such great demand, with your appointment books filled for months into the future, that you are often portrayed in the media as carelessly eager to drug America's children. That's just not true. Please don't be discouraged. We parents whose children's lives have been saved by modern medicine and appropriate psychotherapy wisely administered are grateful to you, and to your colleagues who do the research, and to those who develop and produce medication and other treatments.

We need to stand together and insist upon more federal funding and investment in research on these important questions.

Thank you.

Martha Hellander

CABF Research Policy Director

October 21, 2004

next: More Research Needed on Bipolar Disorder in Children

~ bipolar disorder library

~ all bipolar disorder articles

APA Reference

Staff, H.

(2004, October 21). Concerns for Our Bipolar Children, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2025, April 12 from https://www.healthyplace.com/bipolar-disorder/articles/concerns-for-our-bipolar-children

They call them drug cocktails. They're becoming the vogue for mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. But mixing drugs is still more art than science.

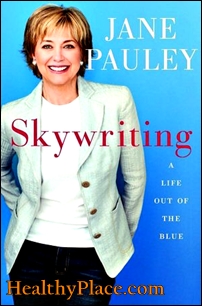

They call them drug cocktails. They're becoming the vogue for mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. But mixing drugs is still more art than science. Treatment with steroids and antidepressants unmasked Jane Pauley's bipolar disorder, the TV news personality reveals in her new autobiography.

Treatment with steroids and antidepressants unmasked Jane Pauley's bipolar disorder, the TV news personality reveals in her new autobiography. Pauley writes that her bipolar diagnosis came a year after treatment for a bad case of hives. Doctors treated her with steroids, often used to relieve the painful swelling and itching of this allergic skin condition.

Pauley writes that her bipolar diagnosis came a year after treatment for a bad case of hives. Doctors treated her with steroids, often used to relieve the painful swelling and itching of this allergic skin condition.

Winter depression, also known as Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is believed to develop from a lack of bright light during the winter months.

Winter depression, also known as Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is believed to develop from a lack of bright light during the winter months. Reporting in the Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, the researchers found "more similarities than differences" between bulimics and partial-syndrome bulimics. In contrast, teens with either form of bulimia differed from those with anorexia on "almost every variable examined," the authors note.

Reporting in the Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, the researchers found "more similarities than differences" between bulimics and partial-syndrome bulimics. In contrast, teens with either form of bulimia differed from those with anorexia on "almost every variable examined," the authors note. A new study conducted at the University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland has revealed that women with anorexia are more likely to have suicidal thoughts than those with bulimia or other disorders.

A new study conducted at the University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland has revealed that women with anorexia are more likely to have suicidal thoughts than those with bulimia or other disorders. The appropriate administration of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder is a challenging clinical problem. Antidepressants can, even in the presence of the administration of an adequate dose of a mood stabilizer, induce mania and cycling. Since there are now several clinical alternatives to antidepressant use in patients with cycling mood, these questions are of great clinical relevance in this difficult-to-treat population. Three studies were presented at the American Psychiatric Association 2004 Annual Meeting that attempted to address these questions.

The appropriate administration of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder is a challenging clinical problem. Antidepressants can, even in the presence of the administration of an adequate dose of a mood stabilizer, induce mania and cycling. Since there are now several clinical alternatives to antidepressant use in patients with cycling mood, these questions are of great clinical relevance in this difficult-to-treat population. Three studies were presented at the American Psychiatric Association 2004 Annual Meeting that attempted to address these questions. Now, as awareness among both the general public and the medical community has risen, more adults are being diagnosed with ADHD. Also known as adult ADD, ADHD includes inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity among its primary symptoms. While about 30% of children diagnosed with ADHD are treated, a mere 5% of adults with the condition are, says Ginger Johnson, senior consultant at Defined Health, a pharmaceutical strategy consulting firm. All this adds up to a potentially huge market for pharmaceutical companies making ADHD medications.

Now, as awareness among both the general public and the medical community has risen, more adults are being diagnosed with ADHD. Also known as adult ADD, ADHD includes inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity among its primary symptoms. While about 30% of children diagnosed with ADHD are treated, a mere 5% of adults with the condition are, says Ginger Johnson, senior consultant at Defined Health, a pharmaceutical strategy consulting firm. All this adds up to a potentially huge market for pharmaceutical companies making ADHD medications. Women with eating disorders who have attempted suicide may have had a depressive disorder long before their problems with food began, the results of a small study suggest.

Women with eating disorders who have attempted suicide may have had a depressive disorder long before their problems with food began, the results of a small study suggest.